1858: Louis Riel & Other Quebec Curios

Part of “Division and Resistance”, 1827-1863

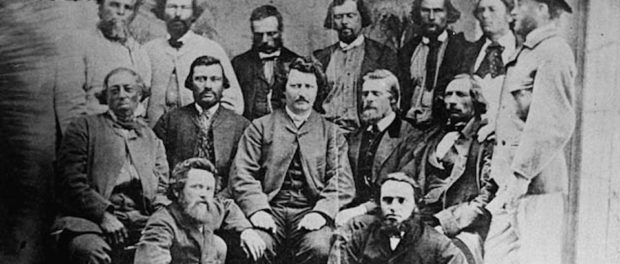

The Provisional Métis Government of 1870. Louis Riel is in the centre. Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada/PA-012854

The Provisional Métis Government of 1870. Louis Riel is in the centre. Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada/PA-012854

In 1858, a young man arrived in Montréal, unknown to many but a select few who had seen his potential as a scholar back in Manitoba. This man, Louis Riel, was supposed to become a priest.

Louis Riel was part of the Manitoban Métis nation, born from a mother who was of French-Canadian descent and a Métis father. The Métis, distinctive in that they were peoples descended from mixed ancestry and had a culture reflective of this distinct heritage, had existed since the arrival of the French-Canadians in New France but had a sizeable population in the territory of Manitoba. From historical records, Riel was a bright child, the eldest of eleven children. Growing up in a devout Catholic family, his early education was far away from the lands of Canada East, back in Manitoba. However, a priest, Bishop Taché, recognised Riel’s potential as a priest. Wanting to get more Métis into the priesthood, he sent Riel to Montréal for formal priesthood training. At the Petit Séminaire in Montréal, Riel would start receiving his training. Arriving in Montréal at only fourteen years old, he continued on the path that he was chosen for. The death of his father in 1864 halted Riel’s studies and he withdrew from his studies, choosing to continue his studies in Montréal but now as a law clerk in order to support his family back at home. He would quickly realise this path was not for him.

Riel’s rise to a leadership position would occur later, in 1868. By then, Riel had returned to his childhood home in Saint Boniface, now a part of Winnipeg. One major political event led him to return to his homeland: the division of Rupert’s Land, a larger territory that also encompassed his home. As the British dissected the territory into lands destined for agriculture, none of the Métis, who were already living on the land and using it for their livelihood, were consulted. Aligning himself with the community of his roots, he would join the Métis cause and fight for the rights of the Métis nation and their hunting grounds. Riel would act, forming a Métis government to go up against the government in power.

Seen as a mad religious fanatic by the English, the Métis saw more to Riel: well-educated, bilingual, and a passionate orator, he was convincing and a strong addition to the Métis’ cause. The French Canadians also embraced Riel’s resistance towards the English and his efforts to protect the French minority in Manitoba. Though Riel was long gone from Montreal by his highly controversial execution in 1885, what he stood for remains a battle for many today and the political divisions that his execution caused also remains another part of the English-French divide in Canada.