The Quebec Easter Rising & Other Quebec curios

Picture this: the First World War, a war which many had thought would have ended years ago, is still going on. News about the conditions current soldiers face is paralysing to most men who are willing to serve; many stop volunteering. It is 1917, Canada is still part of the British Empire, and Prime Minister Borden is desperate for more men to go to the front. It is here that the crisis begins.

For a long time, the Conscription Crisis was seen mainly as a “French Canadian” problem. On a national level, Quebec intellectuals such as Henri Bourassa (Le Devoir) saw Canada as being subservient to Britain when it should act independently. On a social level, many French Quebecers perceived joining the army as another chance to be abused by their Protestant, English-speaking counterparts. Many were needed by their families to support them, such as the eldest sons who were left heads of their family after their fathers had died. Those who did decide to join the army joined the French regiments, namely the 22nd Battalion, which were created to try to prevent the French Canadians join the fight—on the French side. Yet the number of any volunteer soldiers dwindled towards the end of the War, and Canada, out of options, turned towards what seemed to be one of its last few options: conscription.

Borden was insistent, and he and his government worked his way through Parliament’s hoops and passed the Military Service Act. All men aged from 20 to 45 would have to serve in the war until the war’s end, if they were called to serve. To compensate for the men who would leave, Borden also allowed the wives and mothers of the men called to serve the ability to vote as well as denying immigrants who came from the countries that Canada and Britain were fighting against the right to vote. At first, to get out of serving because the Military Service Act was relatively quick and painless, with a majority of men who were eligible for service getting their exemption. But things would change in Quebec City during the Easter weekend of 1918.

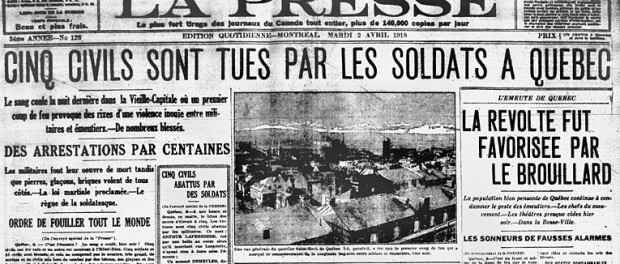

It all started rather innocuously. Police officers asked a young man at a bowling alley for his exemption papers. The man didn’t have them on him, so the police arrested him. Even after the police released the man, the two thousand rioters who had gathered during the time continued, throwing rocks and ice, and attacking police officers. The riots lasted from four days, during which time Borden invoked the War Measures Act and sent in the troops (sound familiar?). On the last day, the Canadian military fired shots; who fired first is still contentious. Five men were killed, and dozens to hundreds injured on both sides. While on no scale to the Easter Rising in Ireland with Michael Collins and the original Irish Republican Army, for the French Canadians involved in the crisis, the anger and bitterness was similar. The seeds of Quebec nationalism were now steadily growing from Bourassa’s denouncement of British imperialism to Lionel Groulx’s “Quebec independence” edition.

For all the campaigning, Borden’s conscription would have very little effect on the men sent over to Europe. About twenty thousand out of forty thousand conscripted men ended up going overseas, with another fifty thousand in reserve. The Canadian government would try conscription only once more, with similar results, during World War II.

Have a curio you’d like to share or explore? Send an email to T.A. Wellington at [email protected]