MONTREAL THEN: POETRY AND TRUTH

It’s Montreal in the mid-1980s at the annual spring ACUTE conference, an apt name for the Association of Canadian University Teachers of English who have gathered to intellectually dry hump each other for four days. It is McGill University’s turn to host this gathering of the Least Employable Academics of Any Discipline.

I am a freshly minted Ph.D., a young buck out to prove his worth. The conference is not only a job market but also a whorehouse. Young prospects are prodded, ridden, abused, all in one great circle-jerk of posturing, sniping, and academic one-upmanship where only the strong survive. A lucky few will be offered one-year positions; the rest will slink back into academic obscurity, hoping for some grant to tide them over for another year so that they can escape the real world of shit jobs and 9-5 zombification.

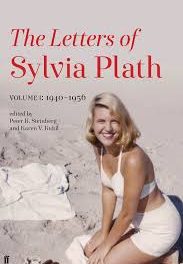

I am on stage before fifty or so of the best minds of my generation, sweating over some paper I have written entitled: “Phallic Exclusion in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath.” The moderator, a benign Emeritus Professor of seventy from UBC, soon to retire, has introduced me, calling my paper “brilliant,” obviously never having read it. In fact, he follows my droning voice, turning each wearisome page of the copy I had previously faxed him until he falls into a peaceful sleep. But there is someone in the front row actually listening and frowning.

I remember her as the Feminist critic from the University of Toronto who has made a name for herself with her controversial book, a study of Hemingway’s collection, Men Without Women, entitled Alone with My Elephant Gun: The Jack-off Artist as Existential Hero.

When I finally finish my paper, there is polite applause, and I feel some release. My sphincter muscles have finally ceased to contract, and I feel the welcome prospect of my third bowel movement of the day after the obligatory question period. I think of Oedipus and how he must have stood, waiting to answer the riddle of the Sphinx. (That’s when your sphincter contracts—get it?)

There is a long, painful silence and no questions. It is twenty minutes to Happy Hour sponsored by the Society to Honor Suicidal Confessional Poets, and everyone is bored and tired. Relieved, I gather my papers when the Feminist critic barks:

“What you have said is extremely dangerous.” Suddenly, there is silence and hushed anticipation. She continues: “You’ve dared to use works like the ‘truth of her words’ — how can you talk about truth, when there is only language. Haven’t you read your Foucault, Barthes, and Derrida?”

She’s hostile now, shaking in rage and ondignation.

I say nothing, but only stare. Fact of the matter is, I want to tell her about Olson’s essay “Poetry and Truth,” Goethe’s “Dichtung und Wahrheit,” and Keats’ “Negative Capability,” but I am tongue tied. The discipline of English is no longer about the sacredness of words, about life-lessons to be learned, about the tragedy of human suffering, but about intellectual pyrotechnics and verbal mind games. It’s not about the tragedy of Keats writing against time or about traveling cross country for seventy two hours to find eternity, but about praising long-winded, obscure critics who, when asked:

“Have you read Dostoevsky?” Reply: “Has Dostoevsky read me?”

I remain silent, and the room slowly empties. She walks up to me, invading my personal space, thrusting her breasts aggressively into my chest.

“Well….?” she demands.

“You’re staying at the Delta on President Kennedy, right? How about me coming by and us raiding your mini-fridge and then doing unmentionable things to each other?”

She nods and refastens the top button of her blouse, blushing almost demurely.

Goethe, Keats, Olson, D.H Lawrence, Hemingway and the Wiser Brotherhood of Great Dead White Males lift their glasses in a toast of approval and assent, their steady applause echoing faintly in the recently emptied room.

Actually, I stammer something about maybe misreading some of Plath’s poetry, eyes downcast meekly before her wrath. Then, I wish her an enjoyable rest of the conference.

And after my third beer, I realize that I hate myself.

.