My Name is Aquil, and I am Canadian! : Canada’s Self Portrait Project

Remember those “My name is Joe and I am Canadian” ads? Well, other than thinking that the beaver is a proud and noble animal, what does it mean to be Canadian? 23-years-young visual artist Aquil Virani and youth workshop facilitator Rebecca Jones decided to address this question in a cross-country art project entitled Canada’s Self Portait. The project has them collecting sketches that respond to the question what does it mean to be Canadian and transforming them into a single art piece. Canada’s Self Portrait launched its “>Indiegogo campaign on July 1 and the cross-country journey starts in St. John on July 20 and ends in Victoria. Virani talked to me about the project and how he got started making collaborative art.

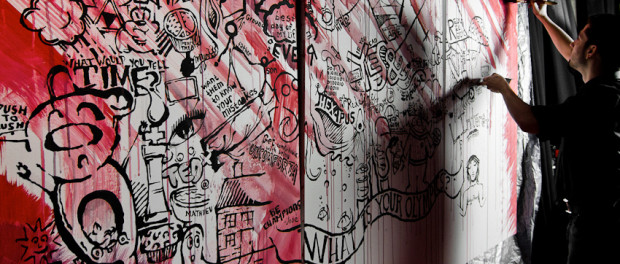

Virani has made collaborative art for several years, coordinating around 12 significant pieces so far. “I find creating art is a great way to connect people and bring communities together,” he says. His pieces are created from sketches that people draw on scraps of paper that Virani then copies onto a larger canvas, shaping them collectively into bigger images. “I did this at schools, colleges, universities, and with younger students. I wanted to take it to a different scale. Instead of one school, making it Canada-wide is a nice challenge and motivates me to bring out my best.”

Together with Jones, the two will be taking trains across the country asking people to fill out a survey form (which can be accessed here) and collecting sketches that answer the question, “What does being Canadian mean to you if you had to draw it?”

The goal is to get sketches from the general public in all 13 provinces and territories and exhibit the finished work at the National Gallery. Though the two wanted to visit the territories, it proved to be too expensive. “We tried to fit it in, but it cost double the trip across Canada to go to Whitehorse, Yukon, Iqaluit.”

Virani doesn’t use the images directly, but instead interprets them through his own hand. “I put the piece of paper [with the sketch] in front of me and reproduce it myself. The way I think of it is that I am a maestro. I give them one unified look.” He does this because collaborative artwork tends to end up muddy or inconsistent without someone to bring them together.

“I wanted to find the balance between freedom and restriction when giving a participant something to do,” Virani explains. “Leave out a bunch of paints and a canvas, and you’ll get a mismatch of colours and then it’ll turn brown. Someone will write ‘Michael has a big penis’ on it. You have to strategically structure the participation. I found giving someone a prop, an informal sketch, was a great way to get something significant, and not too daunting and hard to screw up.”

Though Virani is the filter through which the sketches go, he explains “My main goal is that if they were to see their work, they would recognize it. So I will sometimes change the angle, the scale, the proportions, but the general look of it is the same. They feel like they’re part of the project, and integrated into the broader whole.” Virani also adds washes of colour to the final piece, something the original sketches do not have.

Virani has certainly seen penises and hate messages that don’t align with the spirit of his collaborative projects, but he evaluates each sketch. “It’s case by case if I keep a drawing that is not appropriate,” he says. He often includes them, though. “I might write it very small. The lines I draw might bleed into another drawing. What I like about including the more inappropriate ones is that I’m allowing people to participate in the way they want. When we have elections, not everyone votes, some people spoil ballots. These inappropriate submissions are like spoiled ballots. If you’re choosing to put this in, I’ll respect that.” However, he adds that only around 1% of the submissions are inappropriate.

Jones’ role in the project is more about logistics, but her background entails brining people together and addressing identity. “She’ll go into schools with interesting beliefs about sexual orientation or racism and do workshops. That ties into what it means to be Canadian, given the diversity of what it means to be Canadian. We both have an interest in bringing people together,” says Virani.

The question of Canadian identity intrigued Virani early on. “I, like a lot of other Canadians, have parents born elsewhere. My mom in France and my dad in India. I grew up as this Canadian kid who had a weird identity crisis. I played street hockey when I could and then we would watch Bollywood movies at local Indian theatre, and then I’d go to school and I look like a white guy who is ethnically ambiguous,” he says. “If I’m calling myself Canadian, I have to know what that means.”

“The main point was that I was unwilling to accept definitions we get from textbooks and companies. There are political interests at work in a textbook. We’re getting at the real Canadian identity by experiencing it ourselves.”

Virani and Jones begin their cross country journey on July 15. Their indiegogo campaign that ends July 24 can be reached “>HERE. The form to participate can be accessed HERE.

2 Comments on My Name is Aquil, and I am Canadian! : Canada’s Self Portrait Project

Comments are closed.

:) Reminds me of when you got published in (was it the Sun?) with your article on becoming a Canadian! Who was that favourite hockey player of yours at the time?

Mark Recchi.