1783: Benjamin Franklin Tries to Claim Canada & Other Quebec Curios

Part of “A Colony in Transition, 1763-1791”

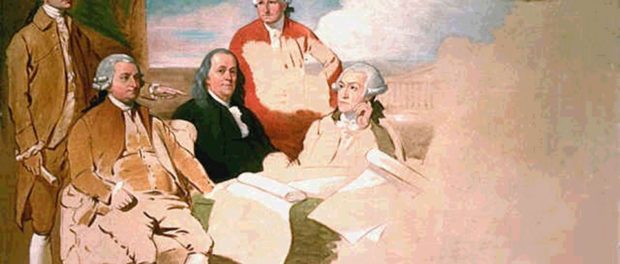

Benjamin West's portraits of the American delegation of the Treaty of Paris. The British refused to sit for the portrait, hence it remains unfinished. Left to right: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and Temple Franklin (Benjamin's grandson).

Benjamin West's portraits of the American delegation of the Treaty of Paris. The British refused to sit for the portrait, hence it remains unfinished. Left to right: John Jay, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Henry Laurens, and Temple Franklin (Benjamin's grandson).

By the time the American War of Independence ended and each party sent their respective delegations to conclude peace treaties with one another, tensions were high even amongst the people in their delegations. While popular history talks mostly of the treaty between Britain and the former Thirteen Colonies, there was another treaty that Britain concluded with France and Spain. We call the treaty that Britain concluded with the Thirteen Colonies the Treaty of Paris, while the other treaty that Britain concluded with France and Spain are called the Treaty of Versailles. Paris and Versailles would be the popular locations to conclude a treaty, with Paris notably being the location of treaties following the abdication of Napoleon. Both Versailles and Paris would also be locations where countries negotiated the end of the First World War.

Coming back to the end of the Revolution, the Americans-to-be would send their own delegation to Paris. Some household names would be part of this war of words: John Adams, the future president; Benjamin Franklin, whose name is perhaps self-explanatory; John Jay, another Father of Confederation; and Henry Laurens, the President of the Continental Congress and freshly out of the Tower of London after being captured by the British during the War. Between the four, there were disagreements between these famous men. John Adams didn’t care for any of his fellow delegates. Benjamin Franklin didn’t like John Adams and had his own personal problems to deal with, including a Loyalist son. John Jay didn’t like Franklin or Adams’ position on the French. Henry Laurens were caught in the middle of all this political intrigue and only participated in the beginning of the negotiations; his signature cannot be found in the final document. Originally, Thomas Jefferson was supposed to join the delegation, but his travel plans failed. During the negotiations with the British, Benjamin Franklin pushed for the British to give them the Province of Quebec and other Canadian territories to America. Perhaps he knew that the British would not settle for that.

Parties to the British delegation to the Treaty of Paris were two men named David Hartley the Younger and Richard Oswald. These two men were appointed by King George III to negotiate a deal with those dastardly Americans. Initially, it was to be with these two men that the Americans negotiated, along with the French (Spain did not want to give up fighting yet because they wanted Gibraltar back from the British). However, the Americans saw they might be able to get a better deal if they negotiated with Britain alone, and France was kicked out of the negotiations with the Americans. Some of the power behind the British delegation came from the British Prime Minister himself, William Petty, the Earl of Shelburne (later the Marquess of Lansdowne). The Earl, sensing he could secure future economic ties with America if he played his cards right, was generous with the land negotiations between the Americans. Fortunately, he didn’t allow Benjamin Franklin’s suggestion.

There was no Canadian delegation, as the Province of Quebec and surrounding territory still were colonies to Great Britain. In addition, unsurprisingly for the times, there was no Native American delegation to these talks and in consequence, much of the Native lands were ceded left and right without any regard to any ancestral or territorial claims the Aboriginal peoples might have had. Next week, we’ll look at the contents of the Treaty of Paris and what it meant for the Province of Quebec.