1838: Pied-du-Courant and the Durham Report & Other Quebec Curios

Part of “Division and Resistance”, 1827-1863

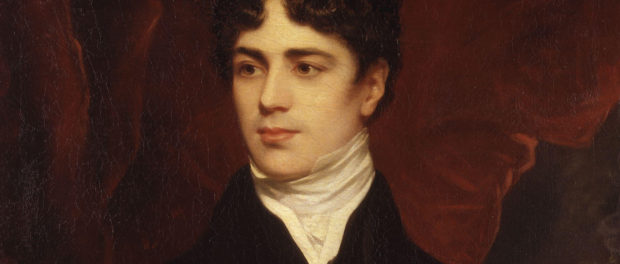

Detail of a portrait of Lord Durham by Thomas Phillips, date unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery (NPG 2547).

Detail of a portrait of Lord Durham by Thomas Phillips, date unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery (NPG 2547).

The rebellions in Lower Canada came to its final, bloody end in 1838. With the defeat of the Patriotes in Odelltown, many Patriotes were imprisoned in Pied-du-Courant Prison in Montreal. John Colborne, the victor in both Saint-Eustache and Odelltown, imprisoned the remaining Patriotes and ordered twelve of them to be publicly executed by hanging. Many others were transported to Australia, then the penal colony of Britain, though some were released under condition.

The executions, which would continue into the following year, would mark the end of the Lower Canada Rebellions. Loyalists would hope that with these public executions and deportations that the stability of the British Empire would be restored. Some, however, became more adamant on assimilating the French Canadians. It was with this political and social climate that another Englishman, John George Lambton, Lord Durham, came all the way from London to do a post-mortem of what could have caused the Lower Canada Rebellions as well as their counterpart rebellions in Upper Canada. Newly appointed the Governor-General of British North America, he set out to work in 1838. The Report he would create as he investigated the causes of the Rebellions, however, would have repercussions for far longer than he was Governor-General.

Durham’s report was both controversial and a product of his times. Believing that the English-speaking people were of a superior “race” and the French-speaking people that of an “inferior” one, he recommended something that was accepted by the Loyalists: that both Upper and Lower Canada be united into one colony so that the French-speakers would gradually be assimilated into the country. While Durham noticed that the French-Canadians had their own language and customs, he believed that the preservation of this culture would be detrimental and would have little on the economic and political development of the colony, two things he believed to be important for its survival. His other major recommendation was to grant responsible government to the Canadas, which was one of the causes that the rebels in Upper and Lower Canada were fighting for. This recommendation, however, was not accepted. Called back to Britain due to disagreements about this point and others (including a recommendation for an early form of municipal government), he was Governor-General for less than a year and went back to England almost as quickly as he had come to Lower Canada.

One of the only recommendations followed up from the Durham Report would be the unification of the Canadas. Responsible government, the other major part of his report, would be an accomplishment that would occur much later.