Impressions on La cour des ossements by André Lemire

From June 7 to August 31, at the intersection of Côte-Saint-Antoine and Botrel Street, one may discover an exhibition by André Lemire at the Maison de la Culture Notre-Dame-de-Grâce. Previously exposed at the Espace Pierre Debain, La cour des ossements remains free of access to the general public. Curious visitors may wander through an array of demolished houses with white wooden walls and green, mossy patches at the surface. This symbiosis between nature and the human-made world struck me the most when I visited the grounds on the opening day. Indeed, the broken sculptures demonstrated architectural harmony, enhanced by unpredictable —perhaps chaotic— compositions yet soothing colour codes, namely the contrast between the proliferating vegetation on white or dark brown facades.boney

Contextualizing his work, Lemire defines the ossements as “[…] a site of perpetual transformation, with changing geographies, where nothing reaches a definite end.” For example, within the milieu of spectacles, events, performances, and circuses, the boneyard designates a place of perpetual transition, where destitute material waits indefinitely to acquire a newfound purpose, frozen in a deconstructive process to be reborn again. I carried this artistic and cultural diversity of shifting meanings while venturing into this quiet and intimate exhibition.

The first work exposed is a strange TV setting. Inside the wooden frame are contained white planks and pieces of wooden material representing the miniature of a broken house, which rests on soft cotton fabric. The title La cour des ossements figures right above the TV. There are little holes on the front of the television, where buttons should be, to allow visitors to touch the soft, mushy, cotton-candy tissue carefully placed inside in contrast to the smooth wooden surface of the outside, making the artists’ overall work very interactive.

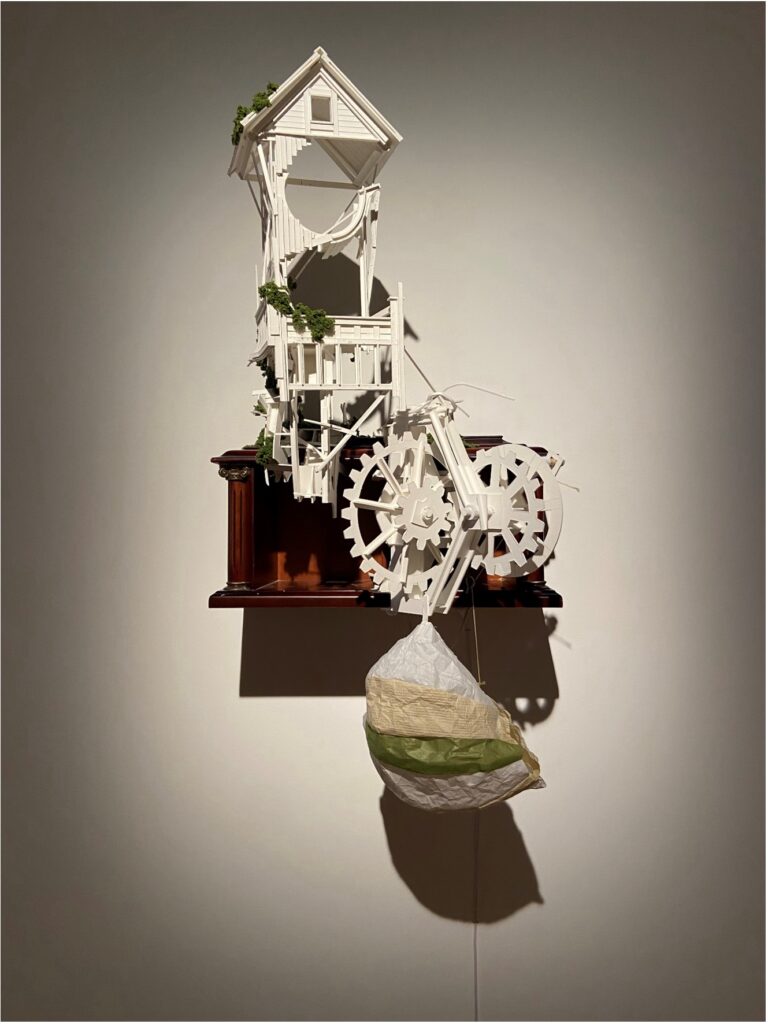

These interactions between the natural and artificial realms are consistent throughout the artistic display, for textured representations of growing moss adorn the facades of demolished house maquettes integrated into real-life household furniture. More than once, the natural world embeds into that of technological advancements, and the reverse process happens simultaneously. Although interconnected, not one sculpture resembles another, each of them a place of its own. I was surprised by the varied media and materials used in their construction. For instance, the second artwork depicts a cloudy, cottoned texture pointing three diagonal lines upwards, as if elevating the work to the sky. It foreshadows the heavenly magic of the general exposition.

The final techniques employed by the artist utilize environmental settings. Light and shadow emphasize onstage round structures, while sound and movement act as a shock through the inner workings of the automated gear. All around, the boneyard, with its mechanical work and delicate forms, is a comprehensive artistic craft where the remains and rubbles of the past evolve into present beauties and constant reconstruction.

Interested visitors may —gently and discretely— touch and take photos of the sculptures. The artwork is not at a distance; it becomes one with the people. This embedding of the object in the subject places the observer at the center of the boneyard, perhaps to signify how the human experience is also a transient entity, which may temporarily lose meaning through a recollection of memories, circumstances, and lived experiences.