Robert Bourassa, Associate Professor & Other Quebec Curios

It’s gone to one of those commissions, but it’s all but official: since August, there have been plans to rename the section of University Street between Sherbrooke and Notre Dame boulevard after former Premier Robert Bourassa. Some people denounce it as another attack on having streets with less English-sounding names, and, what’s more, Bourassa was one of the first to turn the attack on the English language by creating one of the first language bills, Bill 22, restricting English instruction. Beyond all the squabbles, it is interesting to look back on some of Bourassa’s career, in politics and also, briefly, in academia.

Politically, Bourassa seems to hold a wildcard status of sorts in the political world. Hardcore federalists think he’s a separatist, while hardcore separatists think he’s a federalist. (What’s a guy to do?) Bourassa campaigned actively for the No side in the 1980 Referendum, but invoked the Notwithstanding Clause (section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms) in order to bypass a Supreme Court ruling that struck down certain clauses of the 1977 Charter of the French Language (“Bill 101”) that declared French the sole official language of the state and primary language for business. But it was the Bourassa government that was the previous step in the language debate. Termed Bill 22, the Bourassa government proclaimed that French would be the official and dominant language, notably in education, but also the priority in case of ambiguity between English and French legal texts (which is more or less the same rule we follow today). Bill 22 is itself an extension of yet another bill from the Liberal Lesage government that tried to promote French in Quebec. The backlash from Bill 22, denounced by Anglophones as going too far and by Francophones as not going far enough, was one factor among many that led Bourassa to lose the 1976 election to the Parti Québécois, to none other than René Lévesque. Bourassa was in political exile, and turned to teaching.

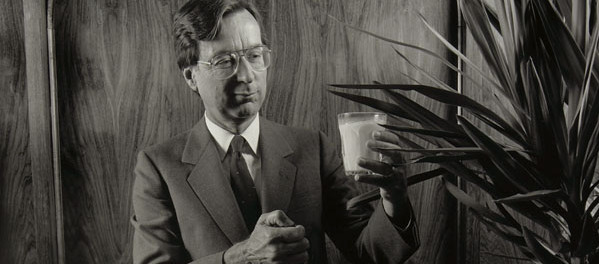

A graduate of the Faculty of Law at the University of Montreal, as well as doing postgraduate work in economics/political science and law at Harvard and Oxford respectively, Bourassa was able to teach at John Hopkins University, Yale University, and the Université libre de Bruxelles, among others, as well as with his alma mater as a law and political science associate professor. I wonder what the lectures must have been like or if his students that were outside the country realized his role in Canadian politics. Surprisingly, or maybe not, not much is written about Bourassa’s years as a teacher. Perhaps it is seen as a footnote in the history of a politician who would eventually return to power as Liberal leader in 1983 and Premier in 1985, but this is a span of just about seven interesting years that ought to have more attention.

In the end, whether a champion or far from it, Robert Bourassa has a lasting legacy on Quebec, and now has another thing named after him. During the announcement, one piece of information that the renaming of University Street most people might have not caught onto. Turns out, one of the streets that Robert Bourassa will be perpendicular to is none other than a street named after rival political sparring partner (buddy?) René Lévesque, former Liberal MNA under Jean Lesage and the leader of the Parti Québécois. This might just be the best historical in-joke ever.