We Have Never Used the Napoleonic Code & Other Quebec Curios

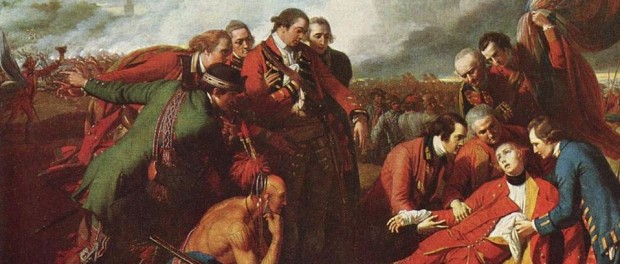

The end of the beginning: General Wolfe, while he did not live to see the British win the Battle of Plains of Abraham, marked the turning point of Quebec's history and the beginnings of English law in Quebec. Detail of "The Death of General Wolfe" (1770) by Benjamin West.

The end of the beginning: General Wolfe, while he did not live to see the British win the Battle of Plains of Abraham, marked the turning point of Quebec's history and the beginnings of English law in Quebec. Detail of "The Death of General Wolfe" (1770) by Benjamin West.

While some of you might have always lived in a castle, Quebec, on the other hand, has never used the Napoleonic code as a system of laws. Think about it for a second. Napoleon’s civil code came into force in 1804. On the other hand, Quebec had been conquered by the British in 1763, almost a half century earlier. It is under British law that Quebec was governed by the time the Napoleonic Code came around, and it is under the British that Quebec gained the second part of its legal heritage.

With the defeat of the French on the Plains of Abraham and the subsequent capitulation of Quebec by the British soon after, the British established a military regime between 1760 and 1763, making British law the de facto law of Quebec. In 1763, France signed the Treaty of Paris, formally relinquishing its rights to Quebec, and indeed most of its territories, except for fishing rights off Newfoundland and the area of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, which remains French to this day. That same year, there was the Royal Proclamation, which declared Quebec was now an English colony, ruled by the King of England. You already knew that, of course, but many inhabitants, however, didn’t seem to know immediately they were conquered. The key to this proclamation, however, was that a piece of territory actually was named the Province of Quebec, curiously extending west of the Thirteen Colonies and around the Great Lakes area.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8yjNbcKkNY

And so came the British, with their British language and their British accents and established their British courts and their British way of life as best they could. I imagine some of the initial exchanges between the English and the French would be à la Monty Python and the Holy Grail. But the British also brought their law of the day, common law, judge-made law. The overall British ignorance of the Paris customs which had officially governed Quebec until the English conquest would be a negligible factor; there were juries for that. In theory, the juries would be chosen according to the background of the parties involved: French juries for French litigants, English juries for English litigants, and a mix of both when both were involved. Yet with British law also came the British criminal laws, including the “innocent until proven guilty” principle, which, apparently, the French enjoyed. The British also brought the liberty to create a will in which you leave your belongings to any person you wish. The latter was so important that the British reinforced this point in the 1774 Act of Quebec. It is here the story culminates, and yet it doesn’t end.

The Act of Quebec was the first point where actual subjects would be attributed to common and civil law, a division that would be roughly translated into the 1867 British North America Act a century later. Common law would dominate what was seen as “public law”, dealings with the state and such. Criminal and penal law, for instance, would be heard exclusively by the British courts and judged according to British criminal law. Civil law, on the other hand, the tradition of the French, would be officially the law with which private matters could be resolved, with the exception of the liberty of testation. To make the French Canadians even happier (this is 1774, after all, i.e. with the Americans just next door starting to become uneasy about Britain), the Act of Quebec further guaranteed the practice of Catholicism and extended Quebec south down towards modern-day Wisconsin.

It seems all fine and dandy, and maybe it was. Common and civil law coexisted. But Quebec was a single civil law place in a growing empire of common law colonies. It would be later, with the creation of the Lower Canada Code, that French law would ensure not only its survival but its propagation.