1713: The Treaty of Utrecht & Other Quebec Curios

Part of “Je me souviens: New France, 1534-1763”

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, far away from New France, in a not-so-little continent named Europe, there was a war going on, and all because of the lack of children. More specifically, countries engaged in a war because of the lack of male children, or rather, the male child. At the very end of the seventeenth century, in November of 1700, the King of Spain, Charles II, died without leaving any heirs, or any children, for that matter. Infirm and handicapped from birth, most possibly from the fact that his family, the Habsburgs, were so closely related that his parents were actually uncle and niece, Charles II was often in ill health. Historians believe that he was also impotent, unable to produce heirs, meaning when he died, the Habsburgs line died with him. Who would succeed as King of Spain?

This sounds not only unimportant but wholly irrelevant to the average New France farmer, who might have not even known that there was a war going on because a king had died. However, the consequences of Charles II’s death unfortunately had its consequences in the New World, because the king’s death meant that many countries, including France itself, now vied for the Spanish throne. France seemed to have a decent claim to the throne, after all: in his will, Charles II named his grand-nephew, Philip, as his successor, and in the event that Philip refused to become King of Spain and inherit the massive Spanish empire, Philip’s brother would get a chance at it. For Philip, accepting the Spanish throne, however, came at a price: he would forever renounce any potential claim he had to become the King of France. This would be a steep price to pay for the grandson of none other than the current King of France, Louis XIV. But Philip accepted, after a meeting held by the Royal Council, though this also had yet another catch to it: Philip was sixteen, and still a minor. Philip’s father had died already, leaving his grandfather, Louis XIV, a man bent on making France the most powerful country in Europe, having effective control over Spain. It turns out that some people didn’t like that idea, especially since that meant that Louis XIV would want to freeze out trade with competition such as the Netherlands and England. War broke out two years after Charles II’s death, in 1702, with the English and the Netherlands countries fighting against France (Spain) and her allies. Acadia and eventually Newfoundland became a centre of battle in the New World. In order to end the war, there would have to be a treaty, or so the story goes.

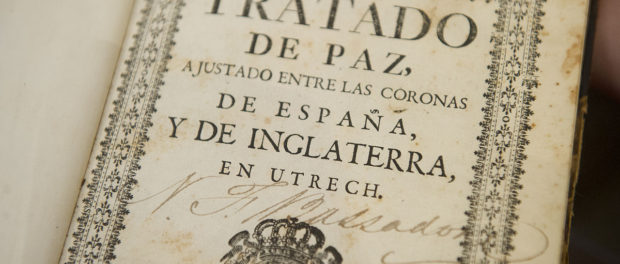

The major idea behind the Treaty of Utrecht would ultimately prohibit any type of unification of the French and Spanish thrones, but, like the war, the treaty had its implications to the territory of New France as well. As part of the bargaining chips between France and England and their respective allies, France ceded Acadia and Newfoundland to England, but retained fishing rights around the coasts of the latter. Even though Acadia would fall into British hands now, the deportation of Acadians would not happen until the 1750s. The French also had to give up the area around Hudson’s Bay. Internally, they also had to compensate the Hudson’s Bay Company for damages that happened to their company.

The Treaty of Utrecht technically meant that war was supposed to stop, the Treaty of Utrecht did little to hinder the outbreak of future conflict, though life in the Quebec region of New France would go on more or less the same as it had been. However, unresolved tensions between the France and England would eventually mean the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, a war that would also have consequences on New France—consequences that some might qualify as devastating.