1838: Another Declaration of Independence & Other Quebec Curios

Part of “Division and Resistance”, 1827-1863

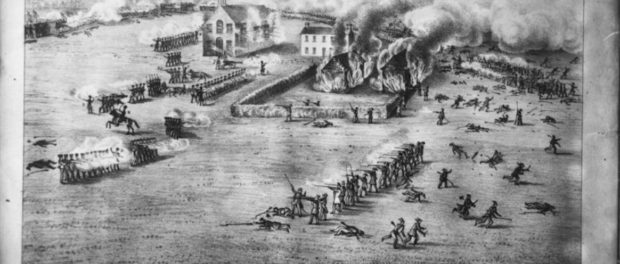

Artistic depiction of the Battle of Odelltown by Edgar Gariépy (c. 1930). Source: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec/SSS1917.

Artistic depiction of the Battle of Odelltown by Edgar Gariépy (c. 1930). Source: Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec/SSS1917.

Lower Canada’s own Declaration of Independence was written by Robert Nelson, an ardent Anglophone Patriote. A look at the document makes it clear that it was modelled after the United States’ own Declaration of Independence, which is not a surprise, seeing that it was Lower Canada’s immediate neighbour as well as the place where Nelson lived. Nelson, like Louis-Joseph Papineau, was forced to flee to the United States in order to escape arrest by Lower Canadian officials. Joined by 300 fellow compatriots in a town in Vermont, Nelson was inspired to write the Declaration of Independence as he and his fellow men prepared for an invasion of Lower Canada. After a series of battles that resulted mostly in defeats (such as in Sainte-Eustache), Nelson and his men believed that their invasion could still result in victory: they hoped that the Americans would be sympathetic to their cause.

Nelson’s document advocated for the abolition of the seigneurial system, separation between Church and State, a guaranteed trial by jury, and voting rights for all men, among other things. His document proclaimed that by the stroke of his pen, Lower Canada was now a Republic and free from the powers of Great Britain (at least it seemed to work with the United States). Whatever support Nelson and his followers might have gained from this document or from their cause from the Americans however, remains unknown in numbers, as they were ordered to cease their activities and put in jail, charged with infringing on the United States’ neutrality laws. Released by a sympathetic judge, they started planning an invasion in Odelltown.

Odelltown was in fact the second invasion planned by Nelson; the first, written around the same time as their own Declaration of Independence, had virtually failed before it began: they had been stopped just as they were entering Canada. Now liberated and on the move again, Nelson and his team regrouped and doubled their efforts in their invasion and formed a secret society, the Frères-Chasseurs, to organise and plan. As the summer of 1838 ended, it seemed that the Frères-Chasseurs and their organisation would pay off. However, as the first shot rang out on an October’s day, the Battle of Odelltown would only last a few hours before Nelson and his team knew they were losing. The Frères-Chasseurs dispersed; Nelson and some of his followers fled to the United States.

Odelltown proved to be the final Patriote battle before the Loyalists would stamp out the rebellion in Lower Canada.