MONTREAL NOW (AND THEN): How Poetry Can Save Your Life

On Friday, May 3rd DC Books held its Annual Spring Launch as part of the Blue Metropolis Literary Festival at Paragraphe Books. Two new books of poetry were being launched by Eleni Zisimatos (Nearly Terminal) and Steve Luxton (The Dying Meteorologist) as well as Keith Henderson’s Sasquatch and the Green Sash (about which I had written in a previous column). As well, two poets who had published previously with DC, John Emil Vincent and Greg Santos, read from their works that will be forthcoming from DC Books in 2020. I had been asked to read an excerpt from my novel, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, also due out in 2020.

The crowd was receptive and generous i their applause, and it struck me how little we do this nowadays: go and listen to poetry or any reading of the spoken word, to watch people bare their souls and affirm the spirit of art. It was heartening to know that there are still others writing and wanting to publicly share their words, and that there were people who actually came to listen and to seemingly cherish their efforts. Writing is something to preserve and to foster, for those who have the courage to put pen to paper are also the ones who preserve the dignity of our culture and confirm our deepest aspirations and longings.

And, yes, poetry can also save your life.

The other day I was walking along Monkland Avenue in NDG. It was a typically gray afternoon, and the low- pressure system had brought on a migraine, so I was struck by a moment of dizziness and a feeling of slight panic. I almost tripped on the pavement, accidentally jostling a young couple who glared at me with abject hostility and walked around me, muttering to themselves. We are not kind to each other.

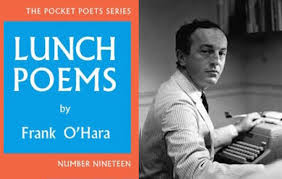

As I finally got my bearings and the moment of light-headedness passed, I thought of New York poet Frank O’Hara and remembered one of his poems into which I substituted my own words: “I wish I were reeling around Paris instead of reeling around Montreal/I wish I weren’t reeling at all….” Frank, whose poems I love and whose poetry inadvertently saved my life.

Years ago, while I was a student at Dartmouth College I was in transit from Buffalo, New York back to Hanover, New Hampshire and had to stop in New York City to change planes with over six hours to spare. So, I took the shuttle to the depot near Madison Square Garden and rode the subway to The Strand (“8 Miles of Books”), a store I had always wanted to visit. Browsing in the poetry section, I found O’Hara’s Collected Poems and sat for a long while, reading. I laughed over his “Lunch Poems,” drooling over his description of eating hamburgers and drinking milkshakes along Broadway and thought of the Olivetti in the display window of a shop where he used to stop to type casual poems during the course of his working day. I thought of the music of Billie Holiday—“Strange Fruit”—Frank, the strangest fruit of all, who, many decades ago had stood in the Five Spot (now gone) listening to her and Mel Waldron on the piano, her contralto voice descending into a whisper, a sob, as he, the poem and I all stopped breathing.

And Frank, killed in the prime of his life by a dune buggy on Fire Island one fateful summer night.

I too wanted to be like him, to see the world’s mosaic unfold and to piece it back together with words. I continued reading, following the rhythms of the poems, losing track of time. When I arrived back at La Guardia Airport, panicking, I found that I had missed my flight and would have to wait for the evening connection. Upon arriving in Hanover at night among the sharp smell of pines, country darkness, and silence, I hitchhiked along an unlit road in the November drizzle that was quickly turning into snow. Finally, a car stopped to let me into its human warmth and the inevitable strained conversation between strangers.

“What do you do?” I asked my driver after telling him that I was a student at the college to set his mind at ease.”

“I’m an insuranc investigator, here to assess the crash.”

“Crash? What crash?”

“Flight 764 out of New York. Everyone was killed on board. Just a few miles from here. A real mess. Seventy-three souls.”

I felt the heat rise in my face and said: “I missed that same flight earlier in the day!”

“Wait just a minute now,” he said, his voice filling the car as he pulled over to the shoulder and turned on the dashboard light. Rummaging among his papers, he pulled out a sheet that had the flight log and passenger list (this was in the days before computers and cell phones) and shoved it toward me.

My name was featured first on the list.

“In the next day or so I will have to inform the families,” he said, his own voice breaking.

Turning away from him to face the dark, I mouthed silently to no one: “Seventy-two — with one still to follow.”

Remembering this, I recall the poet, Greg Santos, at the DC Book Launch just a few weeks ago reading from his forthcoming collection, Dear Ghosts, a poem of that same name, a moving tribute to friends and family who had passed through and out of this life.

A poignant reminder of how poetry can affirm life also by mourning it.