The Phi Centre offers its progressive look at the world we live in with its new exhibition Sexe Desirs et Data (Sex, Desires, and Data). Through multi-sensory exhibits that examine the relationship between technology and sex, visitors encounter a range of experiences related to sexuality, eroticism, and human connection that remain invisible to the majority because they are marginal or happen anonymously, and sometimes both. Today’s technologies, from cam girls to online dating to Snapchat facilitates these spaces, allowing people to express their desires and eroticism with fewer inhibitions.

The dynamic work is a co-production of the PHI Centre and Luxembourg film production company a_BAHN in partnership with Club Sexu. Club Sexu is a Montreal media outlet, that brings together experts in sexology and communications to “create content, campaigns and events that share information about sexuality, gender and intimacy in an accessible, innovative and entertaining way without compromising relevancy.” Many artists and creative directors came together to create work for the show, including Annabelle Fiset, Maude Huysmans, Lucas Larochelle, Sam Greffe, Juliette Langevin, Laura Mannelii, Ianna Brok, Sandra Rodriguez, and Edouard Lanctot Benoit.

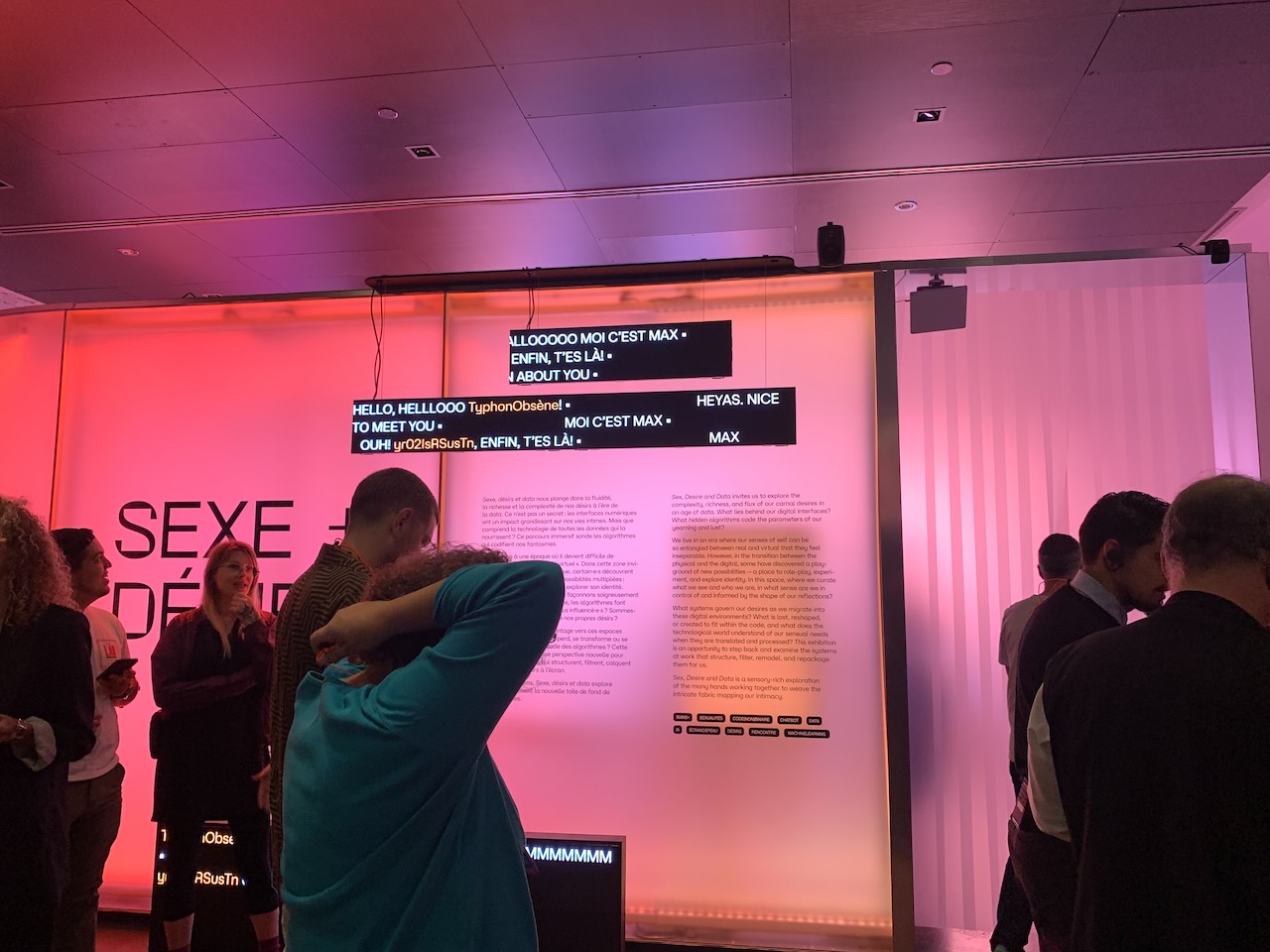

The visit starts off innocently enough by picking a randomly generated username (ScarletHair was mine) in order to communicate with Max, an AI chatbot who makes innuendos and flirts. Max is open to anything and everyone, having a saucy response to nearly everything. He asks some leading questions to establish the relationship, such as whether I’m here for the sex, the desire, or the text. When I respond that all three, he answers back #greedisgood. Everything I write to him is met with a positive response though I didn’t exactly try to test Max’s limits. In addition to being a bright companion, Max also handed out useful facts, such as sexy texts land best when under 40 characters.

From Max, the first stop is Algo Match, a speed-dating game. Taking on the persona of a bisexual man, five players have to collaborate to find him a good match. Will the algorithm be better than our collective selection. Along the way, the players encounter potential partners with whom they can continue “chatting” or basically swipe away in a group vote. The group I played with was not successful (why am I not surprised) as we failed to choose the correct match.

While there are many other surprises along the way, one exhibition that struck me a lot was Hello by Ianna Book. At the centre is a sculpture in white wax, and surrounding it are enlarged screens with ever-scrolling text messaging conversations, each one showing the last message a trans-person received after disclosure. The messages range from rude to respectful, but all are rejections. Having gone through my fair share of online dating as a cis woman and acutely aware of the navigation between privacy and revelation that occur, I was especially struck by how much higher the hurdle is for trans individuals to use this now mundane tool for forming connections. The inconsiderate, dismissive, and hateful messages drove home how technology allows people to act as if there isn’t another human on the other side. I was moved at the persistence and struggle some people face when all they want is to connect.

Another artwork that I enjoyed made use of the platform Queering the Map, a map project of Lucas LaRochelle where people place pins on locations around the globe where their LGBTQ2IA+ experiences have transpired. The goal of the original map is to create a living history and a document of lived realities that are often erased, contested, and invalidated. First, the original map was shown and then visitors entered a room where the map was projected on the wall and different passages associated with the pins popped up.

Finally, I want to mention Confessional, where it was possible to listen to and leave behind confessions. The pre-recorded confessions are read aloud by actors and grouped according to topic. After taking a walk in the secret sexual worlds of others, it’s possible to use technology to express one’s own shadow side of desire by typing it in on a keyboard as part of the database.

All in all, Sex, Desires, and Data is a fun exhibition that tickles the brain and the senses. It is admirably sex positive and normalizes, or at the very least finds commonality, in the many sexual practices that humans engage in and the desires people have. There is no need to feel alone in one’s sexuality, unless of course that is where one wants to be. However, I also noted that the exhibition didn’t have pieces related to illegal, nonconsensual sexual practices which make use of the same technologies, such as sex trafficking and sexual material involving children. This has to be a deliberate choice rather than an oversight. Nonetheless, the taboos and queerness presented through this exhibition are illegal in many places… and in that sense, the exhibition draws a clear boundary and makes a political statement on where sexuality and desire can be socially edgy and transgressive for the mainstream community, but also valid and well within the limits of permissibility.

Sex, Desires, and Data is at the Phi Centre from August 1 to October 31. Information and tickets can be found HERE.