Book of the Month Club: Go Set a Watchman by Harper Lee

“Blind, that’s what I am. I never opened my eyes. I never thought to look into people’s hearts, I looked only in their faces. Stone blind…Mr. Stone. Mr. Stone set a watchman in church yesterday. He should have provided me with one. I need a watchman to lead me around and declare what he seeth every hour on the hour. I need a watchman to tell me this is what a man says but this is what he means, to draw a line down the middle and say here is this justice and there is that justice and make me understand the difference.”

News of Atticus Finch’s 180 from superhero lawyer to evil white supremacist have been greatly exaggerated, but more on that later. Unless you aren’t part of the literary community, or have otherwise been hiding under a rock for the past few months, then yes, the title is not a mistake: Harper Lee has published the novel that had preceded her only other novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. Go Set a Watchman was actually Lee’s draft intended for publication, but the publishers rejected it and told her to rewrite it; what came out of this rewrite was Mockingbird. Watchman is a poor novel as it stands alone, and yet Watchman is fitting as a companion piece to its later incarnation, as a view into a new writer’s mind and a precursor to the Pulitzer Prize winning novel. In Watchman, we get the familiar and the strange: tomboy Scout Finch is now fiery Jean Louise, a young woman in her mid twenties, the product of her father Atticus’ perceived liberal values; Atticus is in his seventies but still active in his community; Jem, Jean Louise’s brother, on the other hand, is deceased, dying suddenly of the same weak heart that killed the Jem and Jean Louise’s mother.

This book was Lee’s first attempt at writing a novel as well as fleshing out the Finch family, and it shows. Exposition is abound: Lee tells instead of shows, preferring to say, for example, that one character was angry instead of showing us a host of symptoms that will lead the reader to conclude by his or herself that the character is indeed angry and not annoyed or pretending to be angry, for instance. The narrative switches points of view without warning, often jumping points of view within one scene from one point of view, to Jean Louise’s, and then to Jean Louise’s thoughts in the person, and sometimes even to an omniscient narrator in order to expose backstory or insights that the characters don’t know about him or herself.

In terms of plot, there are side stories that are left hanging without resolution that could have been delved into further and even provided a lesson (most notably a problem involving one of Calpurnia’s family members). The big confrontation between Jean Louise and her father has paragraphs of speeches from each character that would simply be impossible to make up as one goes along; it is merely a battle of the old South mentality versus the burgeoning liberal thought of the new generation. Only at the end does it feel like a confrontation between father and daughter.

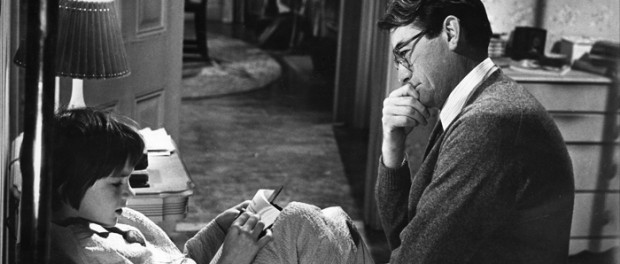

Gregory Peck, the actor that portrayed Atticus Finch in the 1962 movie adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird”, reading the novel. Source: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

As for Jean Louise as a character, I did not particularly like her as I remember Scout. Jean Louise is a modern girl, and unlike her stuffy aunt Alexandra, I don’t care that she drinks, smokes, or wears slacks. Rather, what is disappointing is that this incarnation of Scout is more of a stand-in for the changing mentalities of the United States: she always seems angry at the older generation for their racism and hypocrisy and because they don’t agree with her values, be it her aunt, her uncle, or her father. She says that she hates hypocrites, but she tells her quasi-fiancé numerous times she doesn’t love him romantically and would rather live independently, but accepts his invitations and goes on dates with him. Furthermore, she criticises what she perceives as a destruction of the tenth amendment of the American Constitution by the African-Americans by their deposit of a case on the Supreme Court’s bench, and yet argues passionately that segregation is wrong. In short, while a person can live his or her life as a hypocrite, on paper, Jean Louise didn’t feel coherent. Jean Louise is at her most vibrant when she remembers her childhood: the scenes of Jean Louise as a child with her brother and friends are the most interesting parts of the novel, and unsurprisingly, it is these charming passages that must have led the editor reading this draft to tell Lee to write her story from the point of view of a child rather than a young adult.

Unlike the adult Jean Louise, Atticus remains interesting through both books. The introduction of the racist element in Atticus’ character adds to his complexity as a character and is interesting to see how Lee originally conceived his character: a man who feels threatened by African-Americans who nonetheless represented such a client, perhaps not out of the goodness of his heart. Part of the reason why there was a riot about Atticus’ change in character is that there are two versions. First, there is the Atticus millions of people know and love from Mockingbird, and it is indeed this idol guiding Jean Louise’s actions, thoughts, and beliefs. Then there is the Atticus of Watchman, the aging man attending racist council meetings, partly in order to know who is there, partly because he endorses some of the ideologies espoused in these gatherings. He calls African-Americans infantile and backwards. Atticus’ views are shocking to the modern sensibilities and they should be. However, a reader must place his thoughts in context: sadly, some people like Atticus who grew up with the mentality of the early twentieth century did believe that African-American people would threaten them if the country was desegregated and they thus had to protect their rights as white people. Some people still think that today.

Racism is abound in the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama, and although there is an emphasis on racism against African-Americans, there is plenty of racism against Amerindians and Jews as well in the book that isn’t as well emphasised, but it’s there. It paints a well-rounded summary of the thoughts of the day. There’s a fair share of the “N-word” included in this book which might upset some readers. Yet besides the 1960s ideals, the book also preaches to challenge one’s perceptions. Like Jean Louise must do with the father and what he represents in her life in order to break free, one has to step back from the idols in one’s life and see them from another light–to see them as flawed human beings, a valuable lesson indeed, but one that I felt could have been done with more tact.

In all, I’m not sure what to say about this book. As a stand-alone novel, it is not particularly interesting in that it plods and it is a big soap box from which ideologies preach. As a quasi-sequel, it is mildly interesting, but would need more editing to correct the chronological mistakes inherent in a draft that came before Mockingbird (most notably, Watchman has Tom Robinson, an African-American accused of raping a white girl and represented by Atticus, acquitted instead of convicted). However, as an insight to the writing process and mistakes to avoid for early writers it is indispensable. Recommended, but casual readers should probably loan it from the library.