Book of the Month Club: The Collected Poems of Samuel Beckett, edited by Seán Lawlor and John Pilling

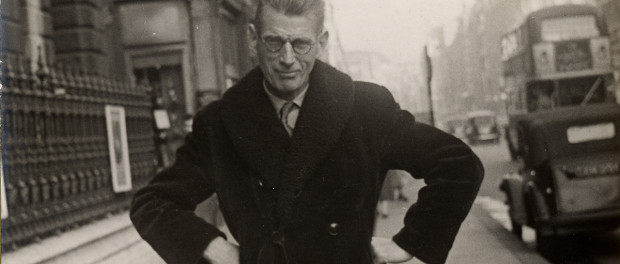

Photograph of Samuel Beckett taken by a street photographer outside Burlington House in Piccadily, ca. 1954. Photo courtesy University of Texas at Austin

Photograph of Samuel Beckett taken by a street photographer outside Burlington House in Piccadily, ca. 1954. Photo courtesy University of Texas at Austin

“Go end there

One fine day

Where never till then

Till as much as to say

No matter where

No matter when”

(“Brief Dream”, c. 1987-89)

Best remembered as a playwright and a novelist, Samuel Beckett was also an accomplished poet. One year prior to the publication of More Pricks Than Kicks (without the final short story), he published his first book of poetry, Echo’s Bones and Other Precipitates. Beckett continued to publish poetry throughout his life, becoming more and more minimalist as he progressed. Yet Beckett is even more unknown as a proficient translator, translating many of his own works from English to French, as well as French writers such as Mallarmé and Rimbaud to English.

Samuel Beckett in a rehearsal for “Waiting for Godot”, 1964. Photo credit: Bruce Davidson / Magnum Photos

Half of the book is Beckett’s writings; the other half is dedicated to a commentary by Lawlor and Pilling. Some highlights of his poetry include an acrostic dedicated to fellow mentor James Joyce, “Home Olga”; a poem about Descartes, his philosophy, time, an egg, and many other topics, “Whoroscope”, originally annotated by the author; and Beckett’s last poems, “Comment dire”, and its corresponding English translation, “what is the word”, still shows its allusions to Joyce in its nod towards Finnegans Wake. On the English version of this poem, Beckett wrote “Keep! for end”, as if it were his wish that it would be the “last words”. Prior to the publication of Echo’s Bones, it was partially true: a long history of publication, traced by the editors, shows that “what is the word” was indeed published: posthumously.

An interesting aspect to Beckett’s later poems is how much they resemble his later pieces of theatre. Both seemed to take a minimalistic turn: Beckett’s poem “mirlitonnades” (c. 1977), for instance, resembles in its minimalism and its hypnotic rhythm his theatrical play, “Rockaby” (1980). Yet the most interesting part is the way Beckett is able to string words together, in such a way as to make the mundane poetic. A good portion of the book also contains Beckett’s numerous works in French, which are as eloquent and masterful with the same eye for wordplay and allusions.

Recommended for Beckett scholars and casual readers alike.