Honour: Interview with Dipti Mehta

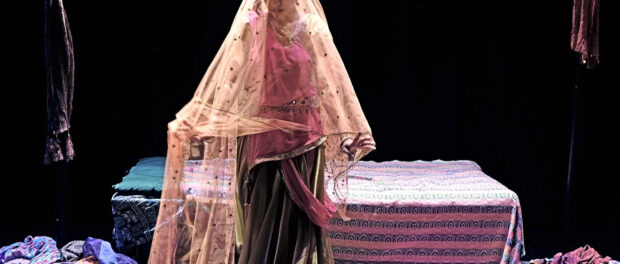

Prostitution, the so-called oldest profession, has many faces. Hollywood and Bollywood have both glamorized and demonized prostitutes and sex-trafficking victims, showing them as anything but human beings with human concerns. Dipti Mehta’s one-woman show, Honour: Confessions of a Mumbai Courtesan, gives a human face to a mother who works as a prostitute as she interacts with her daughter.

Mehta explains that Honour is at heart a story of a relationship between a mother and a daughter who are in the red light district of Mumbai. The mother was trafficked but has reclaimed her power and now has had a daughter. “It’s not a memoir or a memory piece,” clarifies Mehta. “It is a fictional story and a play that evolves. It just so happens to have one actor and seven different characters.”

Mehta was inspired to write the play “for purely selfish reasons” initially. When she moved to New York in 2009, there weren’t many roles for people of colour. “Diversity was just a beginning conversation,” she says. “I wanted to write something based on myself and about relationships that happen in spaces wehre people don’t think they exist.”

While growing up, Mehta was exposed to the red-light districts of Mumbai. “In south Mumbai, when the British left, these red light districts were left behind. Initially the brothels had catered to British soldiers. The women got health care and regular check ups when British were around. But things changed when the British left. These neighbourhoods became crazy.”

Growing up, Mehta passed through the districts, mostly seeing them through the windows of a bus. “I saw these women behind curtains, scantily clad with loud make up, yelling alluring things, all in the middle of the day. There were kids running around. We were told these are dirty neighbourhoods, that you don’t want to go there, that bad things happen to girls there. Byt I was very curious about these people. I didn’t understand what was dirty about them. I had all these questions.”

In India, sex is a taboo topic, despite sex trafficking’s high visibility. “The red light districts are rampant everywhere. It’s in broad daylight. It’s not in the middle of the night or in a place where nobody knows,” Mehta says. “Everybody’s in bed with it.”

Honour allowed Mehta to give expression to the questions she had growing up and couldn’t answer. But more to the point, it allowed her to humanize people who lived in these neighbourhoods.

They’re just people like you or me,” she says. “A mother is a mother no matter what her job, whether doctor, or lawyer, or prostitute. I wanted to tap into that.” In fact, becoming a mother herself five years ago further helped the play grow. “I saw my protagonist in a different way,” says Mehta. “I gave her different facets. Being a mother informed my mother in the play.”

Mehta recognizes the importance of the work. “Most of the issues that we encounter around this are -isms. Racism, sexism. Usually there is a stigma with most of these. We have preconceived notions about people and for women in red light districts – that’s one of their biggest problem. But, society doesn’t let them make a choice, especially for their children. If they have a boy, he goes to world of crime. For a girl, that’s it. Their destiny is pre -determined. That’s sad as a society, that you can’t unburden the weight of your parents.”

Mehta hopes “people see the women of these neighbourhoods as human beings who want to put food on their tables and get the best for their children. They should see past the exterior of these neighbourhoods and the people. The people in these neighbourhoods are very raw. They talk in a rude manner. They’re cursing. But if you go beneath that, peeling the onion layers, you’ll find a child who is trying to survive and doing the best that she or he can.”

“The importance of Honour is that people should see others as human beings. People come to me after the show and they say they loved the mother. They don’t refer to her as the prostitute. That is a shift, because the mother is a prostitute through the entire play. There’s nothing hidden. But when people talk to me, they speak of her as a mother. That’s transformation.”

One more thing Mehta wants her audiences to know is that they collect donations and partner with non-profits to support women who work in the red light districts of India.

Honour: Confessions of a Mumbai Courtesan plays at the MAI from October 3 to 6. Tickets can be purchased HERE.