Leila Alaoui: “No Pasara”: Photographing the Youth Across Morocco

A young Moroccan boy sporting a blue short-sleeve shirt with “France” stitched across the back, sits on bleached rocks by the edge of the Mediterranean Sea. He stares into the horizon – a landscape of hazy mountains, most likely Gibraltar. The tide is calm as delicate ripples dance across the seascape. Anonymous to the viewer, his back is turned as his attention is focused towards another place. Lost in his thoughts, we wonder… what is on his mind?

The photograph is part of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ latest exhibition, Leila Alaoui: “No Pasara”. No Pasara, meaning “entry denied”, is a photographic series taken by the late French-Moroccan photographer and video artist, Leila Alaoui (1982 – 2016), who was killed during an attack by Al-Qaeda in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, on January 2016. Alaoui strove to portray the underdogs of society, specifically undertaking issues of identity and immigration – those who dream and risk their lives immigrating to new lands. No Pasara spotlights young Moroccans who desperately desire to pass through the Mediterranean Sea into European territory.

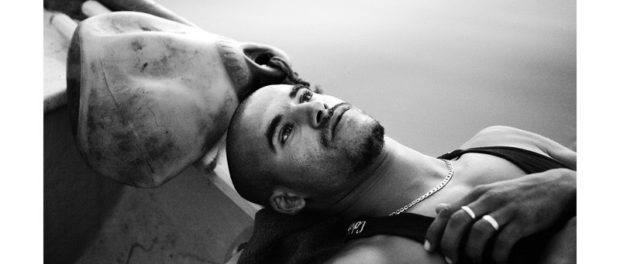

The exhibition is curated through the formalistic elements of the photographs. Upon entering the space, a wall of youthful faces of boys and men confront the viewer, either gazing towards us or pensively in the distance. Towards the wall on the right-hand side, Alaoui places as much importance to the background scenery as the people she photographs, revealing their unforgiving environment, such as mounds of rubbish, ruins, arid land and the vast sea. However, a softness is invoked as the artist clearly considers composition and lighting, enhancing the sense of the picturesque. The second room towards the left of the entrance holds dimmer light. More photographs of young boys in diverse surroundings of dilapidated architecture, an ocean shore, and working in, what seems as hazardous labor, hang on the dusky green walls.

Photographing non-Western subjects, especially as a Westerner, is a delicate matter; one must avoid exoticizing or othering the subject, or in this case, victimizing the subject as history reveals the harmful impact this causes towards an entire culture of people. The fallacy of documentary photography is that, to the viewer, the photographs materialize as truthful – that what one is viewing is an accurate representation of that person a specific moment in time. This can lead towards larger generalizations about a specific group of people while simultaneously reassuring the viewer’s cultural and socio-economic position as they may define him or herself against the photographed subject’s position. Although Alaoui is both European and North African, she avoids a western ethnographic gaze through the photographic lens by conversing with her subjects before taking their picture, rather than simply photographing without their permission. However, this series was commissioned by the European Union in 2008, which makes one question the political intentions of the series. Moreover, the staging of the photographs should be questioned, specifically if Alaoui held the authority as to how and where her subjects should be positioned, or if this was a collaborative process.

Nevertheless, Leila Alaoui: “No Pasara” beautifully captures the children and young adults of Morocco and commemorates the gifted artist who passed away too soon.

Leila Alaoui: “No Pasara” is at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from January 17 – April 30, 2017. To find more information on the exhibition, click here.