1840: The Province of Canada & Other Quebec Curios

Part of “Division and Resistance”, 1827-1863

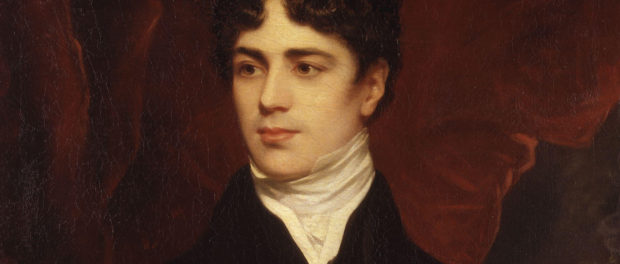

Detail of a portrait of Lord Durham by Thomas Phillips, date unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery (NPG 2547).

Detail of a portrait of Lord Durham by Thomas Phillips, date unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery (NPG 2547).

On the heels of the Durham Report, the British government took some of Lord Durham’s ideas into consideration and in 1840 created a new province, the Province of Canada, through the Act of Union. The Act of Union (officially the British North America Act of 1840), as the name suggests, would bring together Upper and Lower Canada into one Province, but also further divided them. Within the Province of Canada, there would be two subdivisions: Lower Canada would now become Canada East, whereas Upper Canada would become Canada West. The division, however, ran deeper than that.

Maybe the provisions in the Act of Union seemed to be good on paper to the British. Maybe they thought that some of the items in the Act would indeed placate the people in the Province following the Rebellions. In it, we find a standard provision that the monarch in Canada would be able to make laws with the help of the different legislative institutions to ensure “peace, welfare and good government”, a provision that echoed through most Acts created by the British and would again be echoed in yet another Constitutional Act not thirty years later. The Act proclaimed that there would be one House of Assembly with a total of 84 deputies that would be elected by the people of the Province of Canada, half coming from Canada East, half from Canada West. Debts from Upper and Lower Canada would be put together. The House was complemented by an Executive Council and a Legislative Council, who all eventually reported to the Governor General, who had the ultimate word on whether a law would be able to pass. The Governor General would be the one to report back to the British government. The British estimated that with a rapidly growing English middle class and with the implementation of the Act’s measures would the French language would disappear within fifteen years and that the French-Canadians would be assimilated into English culture.

On the ground, the Act of the Union had its opposition on both social and political grounds. The French-Canadians would start the trend of the demographic voting mostly in the same manner. A more important consequence was that the Roman Catholic Church took it into their hands to protect and more importantly, preserve the French-Canadian culture from the hands of the Protestant English. The Church, in essence the new elites of the society, would promote itself as the guardian of health and education as it was in the old days and also promoted a distrust of non-French-Canadians that bordered on xenophobia. On the English side, the elite Family Compact, the counterpart of the Château Clique in English Canada, also opposed the Act of Union because most of their powers would be taken away. In terms of the new Legislative Assembly was seen as disastrous by both sides: the English thought there were too many French-Canadians in the Assembly, whereas the French-Canadians thought that they were underrepresented (there were roughly 200 000 more French-Canadians than there were English-speaking Canadians). The amalgamation of debts was seen as another slap in the face to the French-Canadians as well: prior to the Act, due to the mismanagement of the Family Compact, Upper Canada had raked up their debts, whereas Lower Canada’s Assembly had managed to make a profit.

The political climate remained uneasy during the first few years following the Act of Union, and in day to day life, the usage of “Upper Canada” and “Lower Canada” continued despite the official named change. While the French-Canadians fought for their survival, there were other groups who also emerged, such as the modern concept of the Métis nation, that would also find its voice around these times as well.

Read the Act of Union here.