Drawing on His Roots from Grandmother’s Diary to Tintin: Interview with Philippe Girard

Cartoonists in Québec live in the shadow of two behemoths. On one side, there’s the American comic book industry, with its strong emphasis on costumed heroes and rapid publications. On the other side, Europe’s strong auteur tradition carries with it timeless characters that were a huge part of our childhoods, as well as more mature storylines. At this nexus of influences, Quebec’s comic industry has developed an identity that’s been slowly coming to the spotlight in recent years.

One of these artists making a name for himself is Philippe Girard. The Quebec City native just released a new book called “La Grande Noirceur” published by Mécanique Générale, a publishing house he co-founded with five other fellow creators. I had a chance to speak with him, and talk about his formative years, his influences, and of course his latest opus.

When asked how he started to draw, Girard is hard pressed to pinpoint one moment. “As far back as I can remember, I was drawing. But my first published strips were in my high school newspaper at the Petit Séminaire de Québec, then at CEGEP de Ste-Foy and Université Laval.” Then in 1997, along with Leif Tande and Jean-François Bergeron (aka Djieff Bergeron), he created the fanzine “Tabasko” as his first standalone publication. “This opened a lot of doors for us, and attracted the attention of a few publishers who released our first books. “Tabasko” was our gateway to “real” publishing houses.”

Like many people of his generation, Girard points to Tintin and Hergé’s “clear line” style as an early influence. “That was a big influence for me in the beginning, this really sparse style of drawing. It’s not popular these days to admit the influence of Hergé, but I don’t shy away from it. To me Hergé is to comics what The Beatles were to music; their time may have passed, but no one’s topped them yet. Of course, as my style developed and evolved, I think I moved away from it, and certainly not all my books are drawn in the same style. I hope that from one book to the other, people can feel the experimentation and evolution of my style.”

Along the way, Girard also turned to writing. “I always wrote the texts for my own books, but I also wrote for others, like on “Danger Public” (illustrated by Leife Tande) or the book on Samuel de Champlain that was published to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the city of Québec”. Circumstances also brought him to write a series of novels aimed at young boys. “I was going out with a woman at the time that illustrated children books. She often had manuscripts at her place that were supposed to be aimed at boys, but the texts never felt to me like something a boy would connect with. So one day I sat down and asked myself “What exactly is a novel for boys? What would I have liked to read?” I also needed a break from graphic novels but I didn’t want to stop publishing and was looking for something else.”

So he wrote his first novel, and sent it to a publisher for feedback. “The publisher loved it and released it. That was “Gustave et le Capitaine Planète”, and it ended up being a five book series.” Girard also wrote a sixth one that remains unpublished due to issues with publisher La Courte Échelle, who recently declared bankruptcy with its authors’ copyrights and intellectual properties ending up in a grey legal zone. “The contracts and rights are part of their business assets, so unless the government steps in, or their assets get acquired by an honest and interested buyer, it’s hundreds of writers and illustrators who’ll see their copyrights disappear, and won’t ever see another cent from their creations. It’s a really sad situation.”

His earliest literary influence is the “Bob Morane” series of books by French writer Henri Vernes. “I really loved these books as a teenager, and I’ll admit that from time to time I’ll still pull one out, and find them just as good. And then, ever since my young adulthood, I was really into Latin-American authors like Luis Sepúlveda, Leonardo Padura or Gabriel García Márquez to name a few. I also really like Spanish writer Eduardo Mendoza.” These vastly different influences helped Girard forge a distinctive voice that sets the tone of his books.

One other thing that drives his creative process is music. Growing up, digging through used bins full of records, and discussing and discovering new music with his friends became a weekly ritual. “As a teenager, music at some point was the centre of my universe. This is how I built my identity as a young adult. Sometimes I’ll draw in silence because I need it, but most of the time music accompanies my creative process, and becomes a source of inspiration for me. Music is often a mixture of words and music, just like comics are a mixture or words and pictures. There’s a natural kinship for me between these two mediums.”

As he wrote “La Grande Noirceur”, he tried to build a playlist that his characters would have listened to. “I know that La Bolduc was very popular in that time but that’s all I could find; my grand-mother’s diary doesn’t speak very much of music. But for myself, while working on the book I played a few albums like “Piano Solo” by Arthur H., a lot of Patrick Watson whose introspective tone fit my mood at the time, Cinematic Orchestra, Léo Ferré whose “old French song” vibe helped me capture the mood of the era.”

That diary of his grand-mother was a gift from his father. Girard discovered that she’d kept a journal every day from January 1st 1931 to December 31st 1935. “I realized that we know very little about the daily lives of women at that time. Women would get married at 25 and would seemingly cease to exist. But she did not want to get married. She married at 38 years old, had my father a year later, and when she became a widow ten years later she never remarried. Taking care of a man wasn’t exactly her life plan.”

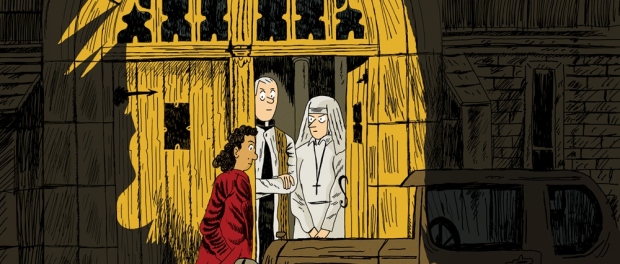

Through her writings, he discovered his grand-mother’s thoughts on a lot of topics. “She had a very harsh opinion on French Canadians. She mentions many times that she’s ashamed to be French Canadian. There was a popular undercurrent that they were inferior and docile underlings, as well as a lot of admiration for the British. She also has words for foreigners that today would be considered racist. And since my maternal grand-mother was of Italian decent, I started to think about how said foreigners would have felt in this environment. So this book uses my paternal grand-mother’s diary to tell the story of my maternal grand-mother. Instead of telling the story from the bully’s side, I chose to tell the bullied’s story. The story takes place at the dawn of World War II; Canada is about to declare war not only on Germany, but on Italy too. So people of Italian origins suddenly were the enemy, and many were imprisoned solely because of their ancestry.”

Many of his books find their roots in his own life. His early “Beatrice” strips were inspired by his daughter,“Killing Velasquez” traces its origins back to a pedophile priest Girard encountered in his youth (he was one of the lucky ones who didn’t become a victim), and “Ruts & Gullies” is a journal of his trip to St-Petersburg that traces a charming portrait of modern day Russia and its people. “Even a work of fiction usually contains a large part of autobiography; it’s just that instead of putting yourself in one character’s shoes, you spread yourself among many. In the end, you’re the character behind ALL your characters. In some of my books, I use what we call auto fiction, where I put myself in the story, but these aren’t necessarily the ones that are the most true to my life. I think my most personal book is “Obituary Man”, this is the one where I presented myself bare the most.”

Girard usually takes a year to complete a book, but his last two, “Lovapocalypse” and “La Grande Noirceur” took him closer to two years each. “At some point I need to take a step back, so I’ll put aside my texts and drawings, and I’ll work on another project until it feels right to come back and finish it, so I might end up with two active projects in parallel.”

Despite writing in French, three of his books have been translated to English (“Killing Velasquez”, “Obituary Man” and “Ruts & Gullies”, which is also the first Canadian graphic novel to be translated in Russian). “All three of my books were translated by KerryAnn Cochrane and she really managed to transpose the poetry of the language. She’s a real wizard of words who manages to grasp everything that is un-graspable. I’m really happy with how these turned out. And I know they put a lot of effort into the Russian translation because I use a lot of onomatopoeia that just don’t exist in Russian, and they spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to translate those. I’ll assume they put the same effort in translating the rest!”

These days, Girard is no longer involved in the management of Mécanique Générale. “After a while we felt we were sacrificing our own careers as authors on the altar of publishing, so we passed the responsibility on to others. Today the company is run by a very capable editor named Renaud Plante who’s able to nurture and help all the authors that work with him. It’s in very good hands.”

The author is not ready to rest on his laurels though: right now he’s doing promotion for “La Grande Noirceur”, but he’s also doing research on a project on attention deficit, and he’d love to revisit the characters from “La Grande Noirceur”, but a little bit later in time, in the middle of World War II.

Girard remains very tuned in to the Montreal English comic book scene which he describes as “totally insane and inspiring,” and he makes frequent apparitions at events in town. He’ll also be making an appearance at the Montreal Salon du Livre that takes place November 19 to 24.

Jean-Frédéric runs Diary of a Music Addict. Check it out HERE.